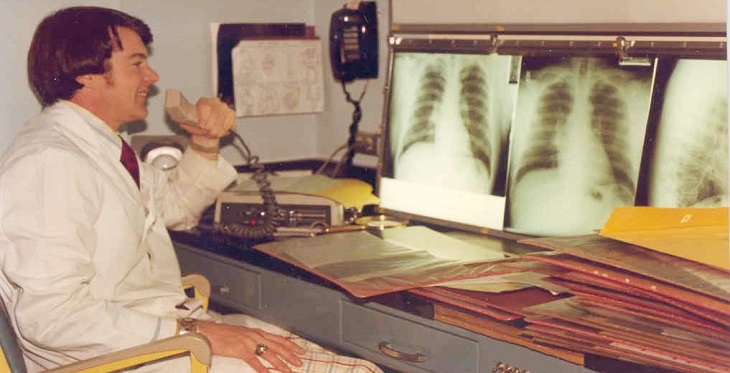

A young version of the author at the view box looking at chest “films” (chest radiographs), circa 1975.

In the Beginning: Going from Analog to Digital

I am now a retired radiologist. I actively practiced radiology from 1971 at the start of my residency until 2014 when I retired as a professor of medical imaging (radiology). A lot certainly changed during that time. When I first started my radiology career, there was no CT or MRI, and ultrasound was very primitive with no real-time imaging. Nuclear medicine did not offer the wide range of studies now available. There was no PET scanning. In fact, radiologists read films on view boxes, actual films, anywhere from 8 x 10 inches to 14 x 17 inches in size.

The standard x-ray equipment was similar today with the same images and routines being used for everyday chest, abdominal, spine, skull, and bone radiographs. The films were enclosed in a metal cassette, exposed, and then taken out of the cassette in a darkroom and placed into a developing machine coming out the other end of the machine developed and dried, ready for viewing on a view box. The films for an individual patient were placed in a large envelope, the film jacket, which was stored in the departmental film library, a large complex of rooms with multiple shelves for holding thousands of film jackets.

Often the individual studies were put into a small envelope for each study which was then put in the film jacket. Naturally, a good part of the time the individual films were haphazardly put into the film jacket and mixed up making it a nightmare to sort through the jacket to find the appropriate prior study for comparison with the present study. Moreover, once a patient’s film jacket was checked out of the department, it was not available to anyone else.

I arrived in Tucson in January 1975 as a newly graduated and certified radiologist by the American Board of Radiology and joined the faculty of the Department of Radiology (now Department of Medical Imaging) at the University of Arizona. Lucky for me, the department was embarking on its world-leading research for converting radiology from the analog world to the digital world under the leadership of Paul Capp, MD, the department head and the late Sol Nudelman, PhD, Professor of Radiology, and world-renowned physicist. Terry Ovitt, MD, who became department head after Dr. Capp, developed many of the research and clinical protocols for digital imaging. My contribution to this was minimal, but I got to go along for the ride.

I am an amateur astronomer, and Nudelman once considered being a professional astronomer. He was a wonderful man who was always smiling and telling funny stories. I was lucky to have gotten to know him. He told me his career switch from astronomy to physics happened after the night he had to lie on his back on a freezing cement floor in an observatory at a remote mountain top while guiding a large professional telescope for a multi-hour photographic exposure. Much of Nudelman’s and his team’s contributions to digital imaging for radiology were applicable to many other imaging applications in science. Nowadays, professional astronomy is totally digital with remote operation of professional telescopes the norm.

Dr. Capp, Dr. Ovitt, Nudelman and others in the imaging teams and research groups in our department presented their results widely around the world, particularly at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) in Chicago the week after Thanksgiving every year.

I first met Dr. Ron Weinstein at the RSNA meeting in 1989. He was a world-leading pathologist in the process of establishing telepathology and advancing the concepts of telemedicine. He attended the RSNA to meet imagers from the University of Arizona to learn about their research on digital imaging and its possible adaptation to pathology. He was also considering becoming the Department Head of Pathology at the University of Arizona, a position which he accepted and assumed in 1990.

Digital imaging in radiology advanced quite rapidly through research done at many institutions worldwide, including the seminal work at the University of Arizona. The main issues revolved around how detailed an image must be (how big an image matrix) for it to keep the same diagnostic applicability as an equivalent image on film.

An interesting and important field of research was the psychophysical aspects of digital imaging and interpretation. This was started by George Seeley, Ph.D, a psychologist based in the Research Division of the Department of Radiology. Seeley was a dear friend, and tragically died at a young age just as his groundbreaking research was garnering recognition. He was succeeded by Arizona Telemedicine Program’s own Elizabeth Krupinski, Ph.D who is currently Professor and Vice Chair for Research, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences at Emory University School of Medicine. She is also a member of the Arizona Telemedicine Program (ATP) being the Associate Director, Program Evaluation, and Director of the Southwest Telehealth Resource Center (SWTRC). Krupinski was the Vice-Head of the Department of Radiology and Head of the Research Division of the department during her later years in Tucson.

Psychophysical research was very important in the early days of digital imaging and in establishing teleradiology as a worthwhile entity. This encompassed many important questions like how much resolution was required to preserve the diagnostic quality of a digital image compared with previous analog film images. How fast a transmission time was practical for a remote radiologist to receive a study, read it, and then send back a report? What quality monitors were required to interpret digital images, what size, what resolution, black and white versus color? How should the monitors be arranged? Should everything be controlled by touch screens or by computer mouse movements? How many cases per hour and for how long should radiologists work without deterioration in the quality of their interpretations? How should quality assurance be performed and reported? How should radiology reports be structured?

Some of these questions have been resolved like required image size and needed transmission speeds. The technology for image production, image processing, and image transmission was greatly improved with rapid advances in computer power and the establishment of fast broadband transmission of data. Many of the questions noted above are still ongoing issues that are not likely to be resolved soon. Psychophysical research continues to be on the frontline of telemedicine.

The Arizona Telemedicine Program was founded in 1996 under the direction of then Arizona State Representative Bob Burns and Dr. Weinstein. Two major goals of ATP were and continue to be “1. To enhance healthcare delivery to medically underserved populations throughout the state using telemedicine technologies. 2. To maintain a statewide Arizona Telemedicine Network to increase access to medical specialty services while decreasing healthcare costs.”

Dr. Capp stepped down as Department Head of Radiology in 1993 and was succeeded by Dr. Ovitt, who continued the research programs started by Dr. Capp. He also worked closely with Dr. Weinstein to establish a teleradiology program. This was intended to serve rural and urban areas in Arizona that had little or no radiology coverage.

Teleradiology in Action

Telemedicine is the delivery of health services over a distance. Teleradiology is radiology performed through the remote transmission and viewing of images. It uses the store and forward approach. The patient’s radiologic study is obtained in a radiology department whether in a hospital, imaging center, or medical clinic, and is stored (archived) on site. It is also transmitted electronically to the radiologist for formal interpretation on a radiologic workstation. That could be down the hall or across the country. The digital images from modern radiology equipment undergo advanced compression and then rapid transmission to a “remote” site for interpretation.

Teleradiology is a bit different than other specialties in telemedicine. The patient cannot receive teleradiology services from their home. Patients must go to where the radiology equipment is situated. It is possible to receive many other telemedicine benefits from one’s home if you have the proper equipment and broadband service, but not teleradiology.

Teleradiology is no different from ordinary radiology other than the patient’s radiologic study is performed at a location separate and remote from the interpreting radiologist. The patient’s physician may or may not be at the same location where the patient has the imaging study. The University of Arizona Teleradiology practice came into being as the Arizona Telemedicine Program was growing and high-speed communication lines were being laid across the state. At this time (1996-2005), computer technology and digital communications technology reached the point where it became practical to switch from analogy film-based radiology to digital radiology only.

The radiology practice at UMC was part of the University Medical Center practice while the Department of Radiology telemedicine practice was part of the combined University of Arizona and College of Medicine Faculty Practice Plan practice. These were two separate legal entities, one basically representing the hospital medical center (UMC) and the other representing the physician practice. These entities worked closely together and had overlapping leadership, but it was necessary to keep teleradiology separate from the in-house practice.

The Department of Radiology Teleradiology practice handled more than 1,000,000 teleradiology cases from 1997 to 2013. During those years, 35 teleradiology sites were served in Arizona and New Mexico. In the early days many of the cases sent to us were actual film radiographs that had been digitized and then transmitted digitally. Later, this became rare as almost all the cases were obtained as digital data from modern radiology equipment.

In May 2011, Janet Major, ATP’s Associate Director for Innovation and Digital Health, and I made a weeklong teleradiology road trip to many of our client sites in central and northern Arizona and in northwest New Mexico. I wanted to strengthen ties with our teleradiology customers, strengthen their ties with the Arizona Telemedicine Program, and put faces to names of places I had seen via teleradiology for several years. I met a lot of interesting people who were working very hard in more rural regions to serve their communities and their patients.

This trip happened to be at the peak of our department’s teleradiology practice. Since then, the departmental leadership and the leadership of the physicians practice plan have directed their attention elsewhere. The teleradiology program is no longer very active. If I were still in practice and responsible for a large teleradiology practice, I would make every attempt to visit our customer sites at least once a year or have someone in my stead periodically visit these sites. Personal visits go a long way for cementing good relationships. This became more evident during the Covid lockdown, where imposed separations isolated all of us more than we would have liked.

Teleradiology Today: Comments and Recommendations

I retired in 2014 and am no longer in active practice. Thus, my advice and recommendations must be regarded with a bit of suspicion and caution. None the less I do follow the field and am still involved with the Arizona Telemedicine Program. What I have to say is mostly common sense and is somewhat timeless.

Teleradiology’s main raison de existence is to cover after hours-nights, weekends, and holidays. There are hundreds of teleradiology companies which provide after-hours coverage. Most of these companies are private entities. Some are academic medical centers which have a teleradiology component of their academic practice.

Some of the large teleradiology companies also offer routine daytime coverage, as well as hard to get subspecialty coverage, such as pediatric radiology, mammography, and nuclear medicine sub specialization. Some provide complete coverage for a clinic or medical center, but most that provide daytime coverage supplement in-house radiology coverage or cover a practice in case of radiologist illness or vacation.

What are the requirements for good teleradiology practice? Of course, the radiologists should be fully licensed and credentialed for the institutions they are providing service. The teleradiology practice should follow all applicable federal and state laws concerning patient safety and privacy. The teleradiology practice must have a vigorous quality assurance program, the results of which are periodically provided to its customers. The image quality on all sides must meet national standards.

Emergent and urgent coverage 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and 365 day a year (24/7/365) is required for a medical practice if Emergency Department (ED) and trauma services are offered. Ideally, an emergent case should be reported within 30-60 minutes from the time the study is received by the teleradiologist. A simple chest radiograph or a shoulder X-ray should be reported in 30-minutes or less. A complex full body trauma CT study from head to toe with thin sections, sagittal and coronal reconstructions, non-contrast, and contrast views, may contain 2,000 images and require at least one-hour for careful study.

The time that is measured is from when the radiologist receives the study on his or her workstation. This is not the time from when the patient is first seen in the ED or the time in which the patient first appears in the radiology department. The teleradiologist has no control over these actions, and many of the delays in getting back a definitive radiology report to a referring physician are caused by patient registration and transportation problems. These are critical issues for all medical practices but are usually out of the hands of the radiologist and unfortunately often are out of the control of the referring physician. Such delays are most frustrating for the patient and for the treating medical team. They can significantly harm the patient and are a continuing challenge in most medical practices.

Routine non-urgent cases should be reported by 5 p.m. the following working day if not earlier. All reports should be in a digital format for easy insertion into the patient’s electronic record. It is mandatory for the teleradiology practice to know where its reports are going and to make sure they are seen by the proper medical personnel taking care of the patient.

There must be an established process between the teleradiology provider and the medical facility for any unexpected, emergent findings to be readily transmitted to the patient’s physician even if a study was not ordered on an emergent basis. This process should also include any significant changes to a radiologic reading found through peer review or when a preliminary reading is finalized and significantly differs from an earlier preliminary reading.

Most teleradiology practices have a series of critical findings, such as an unexpected lung mass, a tension pneumothorax, a bleeding aneurysm, intra-abdominal gas, unstable spine fracture, and so forth for which an urgent phone call must be placed by the radiologist or someone acting in his or her stead to a responsible medical care individual who can attend to the patient. This phone call is in addition to a written emergency report.

An important consideration for any telemedicine initiative is for the personnel doing telemedicine be trained for it and to fully buy into it. There also must be a strong support infrastructure for such an effort. This infrastructure includes but is not limited to the proper equipment and software for the telemedicine communications as well as supporting personnel to schedule patients, to handle the financial aspects of the initiative, to follow-up important findings, and to fix or ameliorate any problems that arise. If one expects the physician, nurse practitioner, or physician’s assistant who sees the patient or interprets the patient radiographs or laboratory studies to also fix communication problems, handle billing errors, and perform routine scheduling and follow-up, the practice will either not last long or will be quite mediocre, due to rapid personnel turnover. This is particularly true if the medical personnel have little say in the initiation of the practice or in its structure.

Infrastructure support for teleradiology has many components. One must start with fast broadband connections to all the referring providers to receive patient studies in a timely fashion. As has been mentioned, all the hardware and software must meet federal and state statues for quality and patient privacy protections. With the alarming increase in cyberthreats in this Covid area, it is also incumbent for the information technology (IT) support to be as much up to date as possible for virus and malware threats. It is assumed the locales where the patient had their radiologic studies performed are responsible for archiving the patient studies and their radiologic reports. The teleradiology provider rarely provides archiving of studies and reports.

Radiologists need good workstations. The design of these has evolved over the years. Usually, they consist of two high-definition monitors for viewing patient images and a third monitor to view the radiology worklist. A fourth monitor is often added for dictating patient reports. The PACS software for viewing and interpreting the studies must be up to date and easy to use. It should be designed for radiologist and chosen by everyday working radiologists in the practice. It must contain or be compatible with the latest voice recognition software as almost all radiology reports are created by radiologists themselves using voice recognition. It is somewhat unusual nowadays for a radiologist to dictate a report and have it “typed” by a transcriber and sent to the radiologist for final approval.

It seems elementary to say, but the patient’s name on the requisition for a study should match the patient’s name, patient ID number, and the study date on the images sent for interpretation. An all too frequent nightmare for the radiologist, the patient, and the referring physician is for the wrong report to be sent for the wrong patient. This error is most likely to happen with very ill patients receiving frequent studies throughout the day and night. Making sure the report being read is for the correct patient for the correct date and time is an ever-continuing challenge. Guarding against such errors must be part of the ongoing quality control measures in place for the teleradiology practice and for all medical practice for that matter.

Radiologists need good patient histories. They need good contact information for the patient’s medical care team. Nothing is more frightening for a radiologist working at home reading an emergent study at 3 a.m., seeing a life-threatening finding, but then being unable to reach any of the patient’s care team.

This is where modern large private teleradiology practices are most efficient. These practices usually have a call center to which the radiologist sends a message to its personnel to track down the patient’s physician, physician’s assistant, or nurse practitioner or someone else who makes sure the patient’s emergent condition is addressed. The radiologist does not have to be on the phone for an hour or more trying to reach someone. That is facilitated by the call center.

The call center can convey the urgent radiology report as well as connect the patient’s physician to the radiologist on the phone. The center is also available to the referring physicians or the medical clinic receiving teleradiology services. If the reports are not being received in a timely manner, if there are IT issues, or if a physician wants to speak directly to the radiologist, that can be easily handled by the call center. The call center can also facilitate the radiologist speaking with the radiologic technologist on site performing the patient studies.

The radiologic technologists are the patient’s and the radiologist’s best friend. A good technologist performs an excellent study, treats patients with the utmost care and compassion, and facilitates rapid transmission of the study to the radiologist. In addition, the technologist is available to answer the radiologist’s questions about the patient’s conditions and study and is usually the one most adept in tracking down the responsible care person for the patient as the technologist knows the local culture best. For any teleradiology practice to be successful there must be excellent coordination between the onsite radiologic technologists and the off-site teleradiologists.

One teleradiology downside to be aware of is there may be poor consistency in radiologic reports from one shift to another. The radiologists are often under considerable pressure to churn out reports, the more they read, the more they are paid. They may be hesitant to spend time discussing a study with a referring physician or spend much effort in tracking down the patient’s medical care team. That is why a teleradiology practice must have a good infrastructure of personnel to support their radiologists. These downsides are no different in everyday in-house practice, but it has been my anecdotal observation that such issues are more frequent with teleradiology.

Knowing the local culture was most important for our teleradiology practice. We covered mammography for several locations. In those instances, we did an urgent review of the mammograms prior to the patient leaving the mammography suite. Mammography is not a procedure one would consider of an urgent nature. Certainly, every patient undergoing breast imaging is worried and wants a report as soon as possible.

In the short term there is nothing on a mammogram that would be a life-threatening finding. Yet, in our practice it was most important to review all the mammograms and breast ultrasounds prior to the patient leaving the imaging facilities. These patients usually were bussed in for their mammography or breast imaging from up to 100 miles away living in quite remote areas in northern Arizona or northwestern New Mexico. They did not have their own transportation and depended on Public Health Service or the Indian Health Service for transportation to their medical appointments. A mammogram that was technically inadequate or which required further views necessitating the patient to return for another visit was an impossibility for someone who lived in an isolated area. It was best to review the study while the patient was available and correct any inadequacies in the study prior to the patient leaving. Otherwise, the patient would most likely be lost to follow-up.

Pediatric chest radiographs can be very hard to interpret. There is a fine line between a normal radiograph for an infant and one showing early pneumonia. It is not uncommon for inexperienced or even lazy radiologists to just interpret a tough study as pneumonia. This way they figure they have covered themselves. It is better to overcall than under call. No, it is not. One must do one’s best.

Sometimes you can’t tell if the study is abnormal, and you simply must say that. Most of the time you can make a reasonable decision. A child who does not particularly look sick in the clinic that receives a diagnosis of pneumonia on his or her chest radiograph may have to be admitted to the hospital for treatment and close observation. This can be a real burden to the patient’s parents who live in a distant rural community and depend on the infrequent or very expensive transportation that goes to their community. Even if they own a vehicle, a two-hour drive to the medical clinic is quite a burden, and there is even a larger burden if their child must be transported from the rural clinic to a larger city where there is a hospital. If the chest radiography does not show pneumonia, the treating physician can feel better about sending the patient home.

The luxury most of us have living in a large city like Tucson is not available in the rural areas in Arizona where there may not be a hospital anywhere nearby, and many small community hospitals have limited ICUs’ and ED facilities. That is why teleradiologists ideally must know the local culture and circumstances and adapt their practice accordingly. It is even better if they visit their teleradiology sites occasionally.

Here's an example of a situation in our teleradiology practice where an unsure or inexperienced radiologist recommended an MRI or other procedure that would have had minimal utility for the case at hand but would have caused enormous time and expense for the patient. MRI was not available at the medical center where the patient was receiving care, and he would have been referred to Albuquerque 200 miles from where he lived. Sometimes, this type of referral is appropriate, but one must be certain this is in the patient’s best interests. This is another example of why it is always good to know the local conditions, and it would be ideal for a telemedicine practitioner to visit the communities he or she serves.

A troublesome downside to teleradiology can occur if the in-house radiologist lets work pile up in the late afternoon anticipating the teleradiology service coming online at 5 p.m. will pick up the load. Not only is this unfair to the oncoming teleradiologist, but it is unprofessional and unfair to the patients whose studies were obtained but put off for later reading. This can also be expensive for the medical center employing the in-house radiologist who is being paid for work not done plus there is payment to the teleradiologist for work that should have been done in-house.

Teleradiology is one of the most developed areas of telemedicine. It offers radiologic care throughout the nation, and its main forte is providing after hours, weekend and holiday coverage. It can supplement or provide complete radiologic care to communities, small hospitals, and clinics where limited in-house coverage is available. It is particularly useful for isolated rural clinics and small hospitals. Like any other facet of telemedicine, teleradiology should be thought out thoroughly and used wisely, and we should celebrate and learn from its history.